“The brain is not concrete… it is always changing.” Mohamed Hesham Khalil

We investigate the work of Cambridge scholarship student, Mohamed Hesham Khalil, which we believe should be integrated into planning and architecture around the world.

Mohamed also brings other top global experts to your ears during this short series of podcasts.

Neurosustainability and the built environment

In this opening episode, architect and Cambridge PhD candidate Mohammed Hesham Khalil introduces neurosustainability—a way of thinking about buildings and cities that asks how everyday environments shape mental health, cognition, stress levels, and long-term brain resilience.

“Sustainability… has to be inclusive and include the brain as well.” Mohammed Hesham Khalil

Jackie and Mohammed explore how the built environment influences us in ways we often overlook: the presence (or absence) of nature, whether our days include movement, how much variety and “spatial complexity” we experience, and how factors like air pollution can undermine health—even in places that look green on the surface.

This episode sets the foundation for the series: a practical, research-informed conversation about designing places that support the brain—not just the building.

Neurosustainability and the built environment

This episode is for anyone who makes decisions that shape how people live inside places—and anyone who’s felt, personally, that certain environments lift you up or drag you down.

“It’s not only about architecture… it’s about the way we live.” Mohamed Hesham Khalil

Architects & designers (especially if you care about wellbeing beyond “light and air” checklists)

Urban planners & transport planners working on walkability, density, public realm, and mobility

Developers & project managers making trade-offs between cost, space, green features, and liveability

Local authorities, policy people, and public health teams looking for stronger links between place and mental health

Sustainability professionals who want a fuller definition of “sustainable” that includes human brains, not just carbon

Landscape architects & public realm designers designing parks, streetscapes, and “everyday nature”

Workplace / facilities leaders thinking about offices, campuses, movement, and stress

Researchers and students in architecture, planning, neuroscience, psychology, public health, or environmental science

A city-dweller feeling burned out, anxious, or mentally overloaded, and wondering how much of that is “you” vs the environment

Someone who wants simple, practical reasons to walk more and get outdoors (without the wellness fluff)

Anyone interested in the future of healthy cities—especially post-pandemic

If your work touches walkability, green space, air quality, or urban stress, this episode gives you language and research framing to explain why it matters in a way people take seriously.

Singapore aerial view

What neurosustainability means, and why Mohammed argues we need it as a framework

How lockdown changed our brains’ daily inputs by shrinking our worlds and reducing spatial complexity

What environmental enrichment is and why it matters for brain health across the lifespan

Why walkability should be discussed as a brain and mental health topic, not only a transport one

How nature exposure and movement can act as protective factors—especially in high-stress urban living

Why air quality matters as much as green space, and how mixed exposures can shift outcomes

What this means for architecture and planning decisions happening right now

Oslo views of water and greenery

“Go back to nature… and translate nature into our built environments.” Mohamed Hesham Khalil

Neuroplasticity: your brain responds to your environment

A central message from Mohammed is that the brain is dynamic. Over time, what we repeatedly experience—movement, stress, monotony, nature, stimulation—can influence how we function and feel.

Environmental enrichment: nature + movement + variety

The episode explores enrichment as a combination of richer sensory inputs, more movement, and more varied experiences—things modern life often strips away.

Walkability is a brain-health intervention hiding in plain sight

When daily life includes natural, repeated walking—especially in engaging environments—it may support brain regions involved in memory, navigation, and emotional regulation.

Green space isn’t a magic fix if air quality is poor

One of the strongest practical points: well-being is shaped by multiple exposures at once. Trees help, but not if the route there is a pollution corridor.

Neurosustainability and the built environment scientific references

3:14

Khalil, M. H., & Steemers, K. (2024). Housing environmental enrichment, lifestyles, and public health indicators of neurogenesis in humans: A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(12), 1553.

Nik Ramli, N. N., Kamarul Sahrin, N. A., Nasarudin, S. N. A. Z., Hashim, M. H., Abdul Mutalib, M., Mohamad Alwi, M. N., … & Ramasamy, R. (2024). Restricted Daily Exposure of Environmental Enrichment: Bridging the Practical Gap from Animal Studies to Human Application. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(12), 1584.

Fares, R. P., Belmeguenai, A., Sanchez, P. E., Kouchi, H. Y., Bodennec, J., Morales, A., … & Bezin, L. (2013). Standardized environmental enrichment supports enhanced brain plasticity in healthy rats and prevents cognitive impairment in epileptic rats. PloS one, 8(1), e53888.

Crouzier, L., Gilabert, D., Rossel, M., Trousse, F., & Maurice, T. (2018). Topographical memory analyzed in mice using the Hamlet test, a novel complex maze. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 149, 118-134.

Khalil, M. H. (2024). Environmental enrichment: A systematic review on the effect of a changing spatial complexity on hippocampal neurogenesis and plasticity in rodents, with considerations for translation to urban and built environments for humans. Frontiers in neuroscience, 18, 1368411.

3:52

Khalil, M. H. (2024). Environmental affordance for physical activity, neurosustainability, and brain health: quantifying the built environment’s ability to sustain BDNF release by reaching metabolic equivalents (METs). Brain Sciences, 14(11), 1133.

Puccinelli, P. J., da Costa, T. S., Seffrin, A., de Lira, C. A. B., Vancini, R. L., Nikolaidis, P. T., … & Andrade, M. S. (2021). Reduced level of physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic is associated with depression and anxiety levels: an internet-based survey. BMC public health, 21(1), 425.

Benke, C., Autenrieth, L. K., Asselmann, E., & Pané-Farré, C. A. (2022). Stay-at-home orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with elevated depression and anxiety in younger, but not older adults: results from a nationwide community sample of adults from Germany. Psychological Medicine, 52(15), 3739-3740.

Coughenour, C., Gakh, M., Pharr, J. R., Bungum, T., & Jalene, S. (2021). Changes in depression and physical activity among college students on a diverse campus after a COVID-19 stay-at-home order. Journal of community health, 46(4), 758-766.

Wolf, S., Seiffer, B., Zeibig, J. M., Welkerling, J., Brokmeier, L., Atrott, B., … & Schuch, F. B. (2021). Is physical activity associated with less depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic? A rapid systematic review. Sports Medicine, 51(8), 1771-1783.

4:17

Khalil, M. H. (2025). The Impact of Walking on BDNF as a Biomarker of Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 15(3), 254.

Phillips, C. (2017). Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and physical activity: making the neuroplastic connection. Neural plasticity, 2017(1), 7260130.

5:30

Elliott, T., Liu, K. Y., Hazan, J., Wilson, J., Vallipuram, H., Jones, K., … & Howard, R. (2025). Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult primates: a systematic review. Molecular Psychiatry, 30(3), 1195-1206.

Zhou, Y., Su, Y., Yang, Q., Li, J., Hong, Y., Gao, T., … & Song, H. (2025). Cross-species analysis of adult hippocampal neurogenesis reveals human-specific gene expression but convergent biological processes. Nature neuroscience, 28(9), 1820-1829.

Spalding, K. L., Bergmann, O., Alkass, K., Bernard, S., Salehpour, M., Huttner, H. B., … & Frisén, J. (2013). Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell, 153(6), 1219-1227.

6.09

Mieske, P., Hobbiesiefken, U., Fischer-Tenhagen, C., Heinl, C., Hohlbaum, K., Kahnau, P., … & Diederich, K. (2022). Bored at home?—A systematic review on the effect of environmental enrichment on the welfare of laboratory rats and mice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 899219.

McCormick, B. P., Brusilovskiy, E., Snethen, G., Klein, L., Townley, G., & Salzer, M. S. (2022). Getting out of the house: The relationship of venturing into the community and neurocognition among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 45(1), 18.

6:54

Khalil, M. H. (2025). Green Environments for Sustainable Brains: Parameters Shaping Adaptive Neuroplasticity and Lifespan Neurosustainability—A Systematic Review and Future Directions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 690.

Khalil, M. H. (2024). Neurosustainability. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 18, 1436179.

8:51

Kempermann, G., Kuhn, H. G., & Gage, F. H. (1997). More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature, 386(6624), 493-495.

Funabashi, D., Tsuchida, R., Matsui, T., Kita, I., & Nishijima, T. (2023). Enlarged housing space and increased spatial complexity enhance hippocampal neurogenesis but do not increase physical activity in mice. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1203260.

9:14

Rossi, C., Angelucci, A., Costantin, L., Braschi, C., Mazzantini, M., Babbini, F., … & Caleo, M. (2006). Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is required for the enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis following environmental enrichment. European Journal of Neuroscience, 24(7), 1850-1856.

9:47

Schmidt, H. D., & Duman, R. S. (2010). Peripheral BDNF produces antidepressant-like effects in cellular and behavioral models. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(12), 2378-2391.

Zhou, C., Zhong, J., Zou, B., Fang, L., Chen, J., Deng, X., … & Lei, T. (2017). Meta-analyses of comparative efficacy of antidepressant medications on peripheral BDNF concentration in patients with depression. PloS one, 12(2), e0172270.

9:56

Toader, C., Serban, M., Munteanu, O., Covache-Busuioc, R. A., Enyedi, M., Ciurea, A. V., & Tataru, C. P. (2025). From synaptic plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a transformative target in medicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(9), 4271.

Yang, T., Nie, Z., Shu, H., Kuang, Y., Chen, X., Cheng, J., … & Liu, H. (2020). The role of BDNF on neural plasticity in depression. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 14, 82.

Schmidt, S., Gull, S., Herrmann, K. H., Boehme, M., Irintchev, A., Urbach, A., … & Witte, O. W. (2021). Experience-dependent structural plasticity in the adult brain: How the learning brain grows. Neuroimage, 225, 117502.

10:14

Khalil, M. H. (2024). The BDNF-interactive model for sustainable hippocampal neurogenesis in humans: Synergistic effects of environmentally-mediated physical activity, cognitive stimulation, and mindfulness. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(23), 12924.

10:54

Khalil, M. H. (2025). Borderline in a linear city: Urban living brings borderline personality disorder to crisis through neuroplasticity—an urgent call to action. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1524531.

Khalil, M.H. & Steemers, K. (2026). Neurobiophilia. Brain Sciences.

12.04

Khalil, M. H. (2025). Urban physical activity for neurogenesis: infrastructure limitations. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1638934.

Bos, I., Jacobs, L., Nawrot, T. S., De Geus, B., Torfs, R., Panis, L. I., … & Meeusen, R. (2011). No exercise-induced increase in serum BDNF after cycling near a major traffic road. Neuroscience letters, 500(2), 129-132.

Pu, F., Chen, W., Li, C., Fu, J., Gao, W., Ma, C., … & Liu, Z. (2024). Heterogeneous associations of multiplexed environmental factors and multidimensional aging metrics. Nature communications, 15(1), 4921.

13:19

Kühn, S., Düzel, S., Eibich, P., Krekel, C., Wüstemann, H., Kolbe, J., … & Lindenberger, U. (2017). In search of features that constitute an “enriched environment” in humans: Associations between geographical properties and brain structure. Scientific reports, 7(1), 11920.

Sudimac, S., Sale, V., & Kühn, S. (2022). How nature nurtures: Amygdala activity decreases as the result of a one-hour walk in nature. Molecular psychiatry, 27(11), 4446-4452.

Harris, J. C., Liuzzi, M. T., Cardenas-Iniguez, C., Larson, C. L., & Lisdahl, K. M. (2023). Gray space and default mode network-amygdala connectivity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1167786.

14.13

Richelli, L., Arioli, M., & Canessa, N. (2025). Neurosustainability: A Scoping Review on the Neuro-Cognitive Bases of Sustainable Decision-Making. Brain Sciences, 15(7), 678.

14:48

Khalil, M. H. (2025). Walking and Hippocampal Formation Volume Changes: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 15(1), 52.

Cerin, E., Rainey-Smith, S. R., Ames, D., Lautenschlager, N. T., Macaulay, S. L., Fowler, C., … & Ellis, K. A. (2017). Associations of neighborhood environment with brain imaging outcomes in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle cohort. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13(4), 388-398.

Sudimac, S., & Kühn, S. (2024). Can a nature walk change your brain? Investigating hippocampal brain plasticity after one hour in a forest. Environmental Research, 262, 119813.

16:32

Khalil, M. H., & Steemers, K. (2025). Brain Booster Buildings: Modelling Stair Use as a Daily Booster of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Buildings, 15(20), 3730.

17:44

Moreno-Jiménez, E. P., Terreros-Roncal, J., Flor-García, M., Rábano, A., & Llorens-Martín, M. (2021). Evidences for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 41(12), 2541-2553.

19:44

Park, S. A., Lee, A. Y., Park, H. G., & Lee, W. L. (2019). Benefits of gardening activities for cognitive function according to measurement of brain nerve growth factor levels. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(5), 760.

20:59

Khalil, M.H. (2026). The Architectural Spatial Complexity Index (A-SCI): A Layout Assessment Tool for Hippocampal Neurogenesis through Cognitive Enrichment. [Forthcoming]

21:59

Shin, N., Rodrigue, K. M., Yuan, M., & Kennedy, K. M. (2024). Geospatial environmental complexity, spatial brain volume, and spatial behavior across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, 16(1), e12551.

24:38

Khalil, M.H. & Steemers, K. (2026). The Neurobiophilia Index. Buildings. [Forthcoming].

Mohamed Hesham Khalil

Mohammed Hesham Khalil is an architect and neuroscience researcher, and a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge.

His work explores the relationship between environmental enrichment, neurogenesis, and the built environment, with the aim of developing a practical framework for neurosustainability in architecture and urbanism.

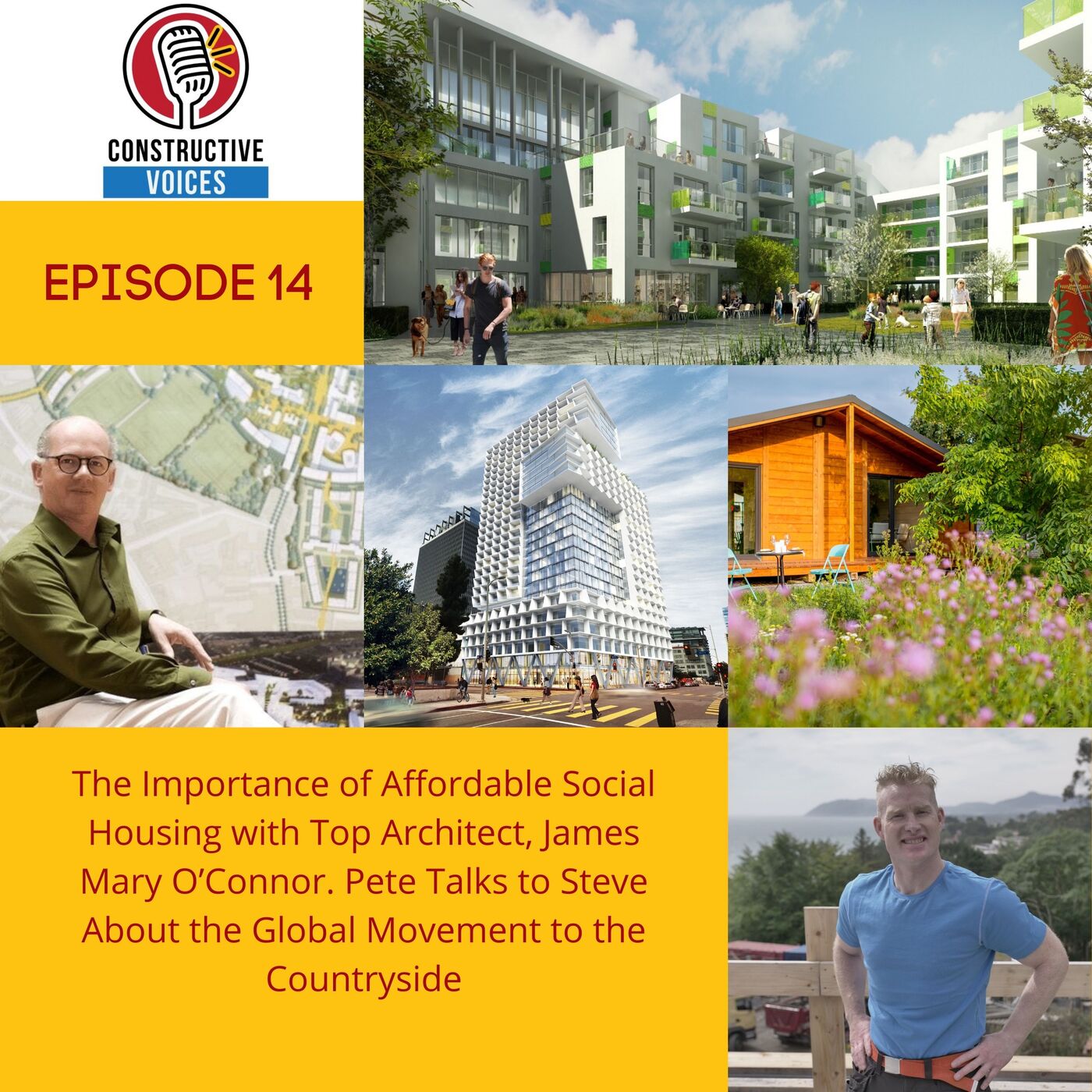

Henry Interviews Top Architect James Mary O’Connor.Following one of our most important episodes to date, James Mary O’Connor, Principal-in-Charge at Moore Ruble Yudell, talks...

This episode features a really interesting conversation between two construction industry experts. Irish builder and TV star, Peter Finn, talks to David Hernandez, Managing...

COP26 saw the first-ever Built Environment DayCOP26 in Glasgow saw the first-ever Built Environment Day. Considering that one of the most shared statistics states...