Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: This is Constructive Voices. Constructive Voices, the podcast for the construction people with news, views and expert interviews.

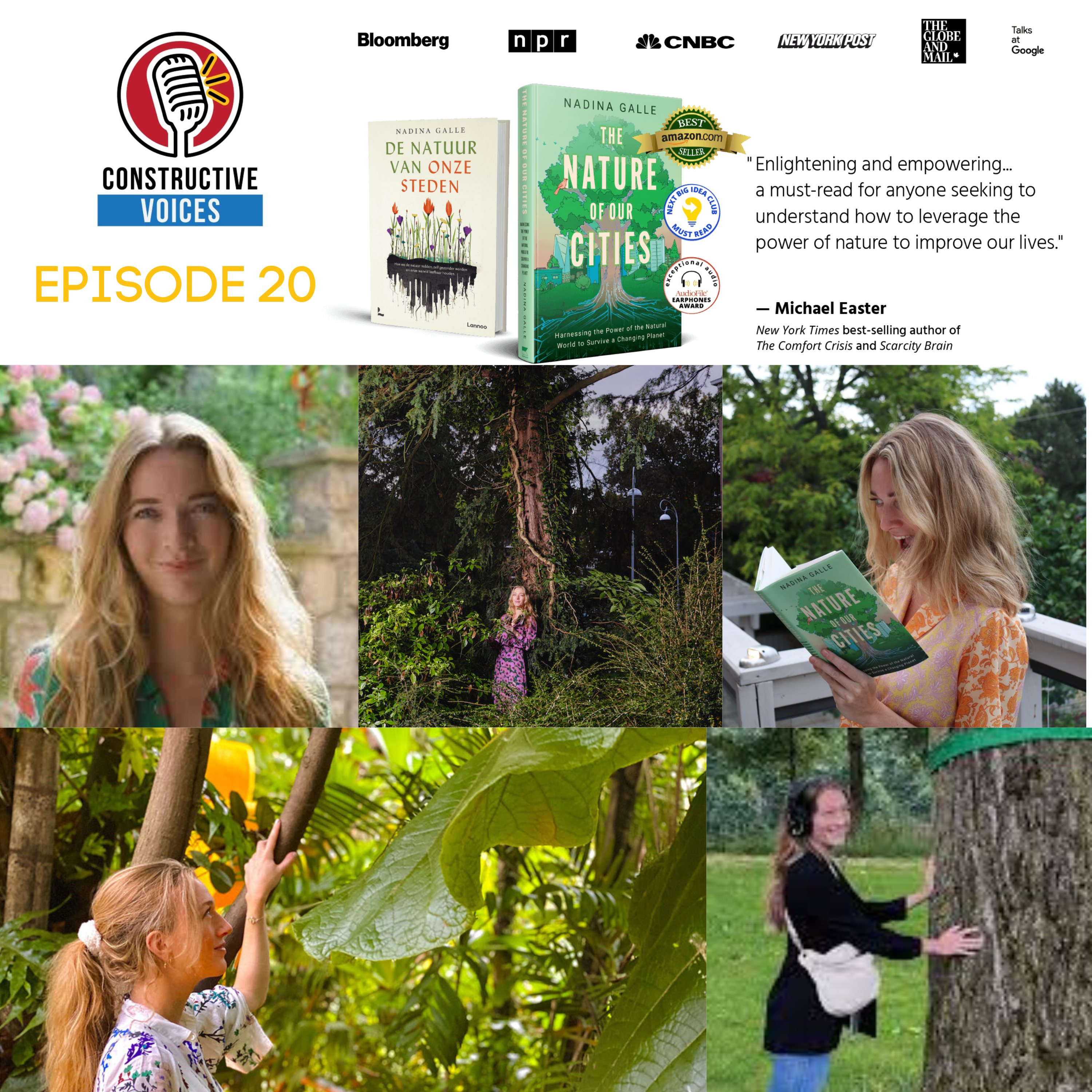

Good morning or good afternoon, depending on what time of the day you're listening to this. This is Jackie de Burca for Constructive Voices, and I am in my final recording with the wonderful author. And she has many other and many other hats that she wears as well. Nadina Galle, who has written this really amazing book which is accessible to all people. And we are now on our final chat, which is really honing in on how nature can affect our health positively.

And we're going into strategies around nature exposure and best practices and so on. Nadina, for those who haven't listened to the other episodes, we're going to obviously give those people a little smack and say go back and listen to the first episode because Nadina does an amazing introduction about all of her work. But for those, for some reason, if they're only listening to this episode, can you give a really brief introduction about yourself, please?

[00:01:11] Speaker B: Definitely. And thanks, Jackie, for having me again. And hello, everybody. My name is Natina Khala. I am a Dutch Canadian ecological engineer. I am a 2024 National Geographic Explorer, and most recently the author of the Nature of Our Cities. How We Can Harness the Power of the Natural World to Survive a Changing Planet.

[00:01:33] Speaker A: Excellent. So we're going to jump right in. Why is nature important for human health? Nadina, I know that is a huge question, but humor me and answer me as best as you can, please.

[00:01:44] Speaker B: Yeah, it is indeed a big question. And I think I'll start with one of the benefits that I think most people can relate to. And that is just the benefit on our mental health. Right. Exposure to green spaces significantly can reduce stress, anxiety, depression. Nature has this really calming and restorative effect, which I think can improve or not. I think research shows us can improve our mood and our cognitive function, and I think in general just helps people feel more relaxed and focused. Mental health is one thing. There's also our physical health. I say nature really promotes physical activity, whether that be walking or cycling or even just playing outdoors. Relax, relaxing outdoors, they say. Research has shown us that regular access to parks and green spices, you know, reduces risks of things like chronic disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes.

That in itself has been really, really important.

But there's also these other things that we may not necessarily think about or see, and those are things like air quality. Having trees and plants can filter pollutants, improve air quality, and thereby also improving our respiratory issues. And overall that comes with that. It regulates temperatures, so it keeps Our cities cool in the summertime. It also keeps our cities warm in the wintertime, which is kind of interesting. It acts as a buffer both ways.

There's a big part of the social connection, which I think goes hand in hand with mental health. But this idea that green areas and parks actually offer areas for community interaction, which especially is important in a day and age where we're dealing with a lot of social isolation and loneliness coming out of the pandemic, that was a huge thing. And in an age where less and less people are going to churches or places of faith, natural areas and green parks really are one of the few areas that we have for having these shared spaces where we can come together and foster community interactions.

And I would say lastly, just to kind of circle back to that first point is, yes, it's important for mental health. But even bigger than that, I think nature and green spaces in our cities, they offer this restorative escape from the noise and chaos and pressures of urban life. And that can be a lot of physical pressures, right? Traffic, big buildings, a lot of asphalt, loud noises. But it can also be the stress of it, right? Busy jobs, busy agendas, you know, stressed out parents and kids, and over scheduled agendas, you know, all of these things without us really realizing at times, can have a huge impact on us. And being in nature, even if that just means taking part of your commute through a green corridor, cycling through a tree lined street, or you know, taking your lunch break in a park, all of those things can have massive impacts on our health. And it feels sometimes tough to kind of, you know, I could go into the specifics of each of these and give you stats and figures about why each of it helps from, you know, helping children not develop myopia, from making sure we have enough vitamin D, from making sure we get enough physical activity. But it almost feels kind of reductionistic to hone down the benefits of nature in this kind of really scientific lens. Because ultimately I believe we came from nature, we evolved in nature. It's part of what makes us human. And I think anyone can relate to this idea that if you're spending the majority of your day inside, you just did not feel well, versus when you spend more time outdoors and in nature, you automatically feel better. And I think that's something that everyone can relate to. And ultimately, I believe we are hardwired to love nature and want to be in nature.

[00:05:38] Speaker A: I do agree with you wholeheartedly.

And I think that, you know, one of the things that it's important that we, we speak about is you've mentioned children in nature, okay, Just for their physical, physical good, to avoid, you know, diseases from the lack of vitamin D and so on. But of course, at a certain point in your book, you do mention that at the time of writing, you were pregnant with Luca. And of course there's, you know, touching on, I suppose, things that a lot of, not just females of, for sure, men are also thinking about these things. Will I bring a child into this world as it is? You know, these are the kind of questions that obviously some people are having. And there's, you know, probably some quite valid reasons for that. This was quite a process for you, I imagine. Adina.

[00:06:28] Speaker B: Yeah, it's really tough. It's a conversation that I hear a lot around me. This very dark fear and lack of optimism for the future, this fear of climate, of climate change, of the effects of it, and this general feeling of this is not a world that I want to bring children into. And that is just. I mean, I get emotional just thinking about that because I believe we're put on this earth to bring more life onto this earth. And I believe that is our purpose at the end of the day. And no matter what form that takes, obviously not everybody has to have their own children if that's not something that they desire. But, you know, bringing in children into the world, whether that be nieces or nephews or stepchildren or adopted children, is such a way that we contribute also to the future of our planet, to the future of the world that we will leave behind for those children. And it's such, it's so heartbreaking to me that there are so many people in the world that feel that that is no longer something worth doing. Because I feel like when you, when you, when you decide that, it also means that you've given up on your own life in some, in some, in some way or another. And I think that the true to test of a beautiful society is those that plant trees and plant natural areas knowing that they will never sit under the shade of that tree. In fact, that's, that's an old proverb that I quote in the book as well.

I believe that being in nature, rather than just focusing on the doom and gloom of climate change, I believe that focusing on nature actually provides this huge sense of abundance, this feeling that there's always more and that there's plenty for everybody and that there's more where that came from, there's more that we can create. And I love thinking about that sense of abundance rather than this sense of fear. And shame and pointing fingers at people that are doing things the wrong way.

I really enjoy, you know, writing and working at this cusp of urban nature because I believe that is the nature that we have in our daily lives that's so critical, but it's also operating from this place of abundance rather than this feeling of. Of shame and guilt.

[00:08:44] Speaker A: Yes, I think that's really excellently pushed. And the other word that will come into my mind in regard to, you know, humans and nature, you know, children being shown by their teachers, you know, that could be their teachers in the school, that could be their teachers in the family and the, you know, the friends, the neighbors, how we can collaborate with nature. Collaboration is the word that comes to mind because in the last episode, you gave some of the amazing examples of your book, the case studies of the likes of snails and, you know, crows and so on.

Nature itself is collaborating with itself. A species is changing its color because it needs to. A species is changing its calls because it also needs to, because of the urban environment that it's living in. So therefore, if humans are collaborating with nature, all of what you see because of your positive work is entirely possible. And therefore, you know, not that there's no need for doom and gloom, but really, that can be quashed and, you know, put down further by just collaborating with nature and encouraging that quickly.

[00:09:58] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. And I think we've. We've.

We've lost sight of that. We've lost sight of the fact that nature is our biggest collaborator. We've lost sight of the fact that nature, I mean, we just listed some at the beginning on the offset of this episode, but nature plays a role in every facet of our lives. I think you could honestly make that argument. And whether that's in the, you know, the resources that we. That we need to build our homes and build our offices, whether that's in their air quality that we breathe and are reliant on every day, the quality of our water, the places that we go to recreate our food systems are entirely based on a healthy balance in our ecosystems with nature. So there's. There's so many different linkages. And ultimately, I think reestablishing that connection with nature is so critical to creating ultimately happy and healthy humans that live on a happy and healthy planet.

[00:10:56] Speaker A: 100%. 100% agree with you, Nadina. So moving on to ecotherapy, which also is, you know, told. Talked about with other names as well. What exactly is it and what other names may we know that by?

[00:11:12] Speaker B: Yeah, I think that some of the most common are probably things like forest therapy. Forest bathing is another one. Is another common one, which comes from the Japanese word as shinrin yoku, which means quite literally to bathe in the forest.

And Japan really was at the forefront of a lot of this because they saw in, you know, rapid industrial revolution, you know, rapid urbanization, a lot of sedentary jobs, which was quite, you know, different to what Japan had been used to previously. They saw massive spikes in mental health disorders and things like stress and anxiety, things that, you know, we can all relate to. And they saw huge benefits of people being out in nature. And of course, you know, the Japanese elders were like, yeah, well, of course, this is where we came from. Of course you're going to feel better and more restorative when you're there. But the government really saw huge potential in that and actually invested large amounts of money to create, you know, to one certify, you know, forest bathing guides to take, you know, even the most, like, staunchest city slickers out into nature, into forests and help them kind of reconnect with the natural earth to hopefully help with some of the, whether it be more severe mental health disorders or just kind of a general sense of malaise that we were talking about just earlier.

And they invested a lot of government money, not until they trained those guys, but also creating barefoot parks where people, you can literally ground, barefoot in the forest, these beautiful hiking trails that you could follow, because they saw that, you know, spending time in forests, it reduces cortisol levels, reduces anxiety. There's even studies that show that it actually increases something called natural killer cells, which are really important in our bodies for fighting off things like cancer. You know, we have these not just mood changes, but physiological changes that happen to us when we're close to trees in forests. It's, it's.

[00:13:15] Speaker A: It's really quite something that it really is something obviously natural killer cells. You know, I think that that just by itself is enough.

It's enough information for me, you know, to be converted, if I wasn't already converted. That's enough, isn't it? You know, when you think about all the horrible diseases you could potentially, you know, prevent by having more natural killer cells, it's amazing.

Nadina, tell us about those forest therapy guides that were trained at Chico State.

[00:13:49] Speaker B: Yeah, so that was a really interesting case study because Chico State or California University is also commonly known. It sits in Chico county, and Chico is right around the corner from Paradise. So where one of the most devastating wildfires happened in US history, and it sits smack Dab in the middle of wildfire County, a country. And this is been really, really.

I mean, for lack of a better word, interesting. Because what you have there is, you have this community, these huge populations of people that have been absolutely traumatized by what they've had to deal with. Their wildfires that have swept through their land, their property, their homes, and in the worst cases, their loved ones. And it has just been so catastrophic and so traumatizing. Many of these, they relate to, actually wild wildfire survivors. They have rates of PTSD in the same levels that you might expect from veterans coming home from war. You know, this is extremely traumatizing. And the thing that's so odd is that the thing that caused this wildfire, nature itself, right? Maybe the spark wasn't caused by nature, but a lot of the buildup of the vegetation, you know, cause its ferocity, how catastrophic it became, that. That nature itself, the kind of the. The instigator of this wildfire, can hopefully also be an area for healing for these people as well. And I think that's. That's. That's what. What made this. These. The training of ecotherapy guides at Chico State so interesting. And I got the opportunity to speak to one of them called Blake Ellis. And she, together with 14 other local mental health professionals, were trained to become certified ecotherapy guides. And the goal was really to then provide comfort to these communities that were impacted by wildfires. And when Blake was telling me about one of these sessions, she was saying that what was so interesting is that for the first time, many of them were able to see trees and these downed trees and the debris that was left, not as this reminder and symbol of death and decay, but actually as opportunity and hope for the future. And I think that's something that's this beautiful parallel that hopefully we can relate back to other fascinating facets of our life as well. And one of the things that Blake said that really stuck with me is that, you know, she keeps. She kept saying when she was telling me about these things is, you know, I am. I am simply a guide. It is the forest that is the therapist. And that is, I think, something that is so central to ecotherapy and forest therapy is seeing the forest as the therapist that it is, and that these individuals that are these certified guides, they are the facilitators that can help take you through. And there's many different exercises. You know, sometimes it's simply sitting and meditating in a forest environment. Sometimes it is literally hugging a tree and coming into contact with some of these. You know physiological changes that can happen to your body. Sometimes it's taking a silent walk, sometimes it's actually just having your therapy session, but you're walking through the forest as you're doing it. So there's many different ways that forest bathing and forest therapy can take place, but the goal is that this venue, the forest, really provides the mechanisms for a lot of this healing.

[00:17:16] Speaker A: I do love the fact, as you say, Nadina, that it is the forest that is the therapist. And I think that's important, you know, not only for those who've gone for the therapy, but also in the sense of any therapy at all. You know, once again, it's human ego that it's like, oh, the therapist is doing this, that and the other for me or for whoever. But actually, at the end of the day, the therapist is only like a conduit, you know, it's a tool. That person is a tool in helping a healing situation. And therefore, seeing the forest as a therapist, I think in itself is just healing, I think.

[00:17:54] Speaker B: Yeah. And I think we have to. It's also important to remind the listeners here, is that we talk about forest therapy, we talk about ecotherapy, but it doesn't necessarily have to be in a forest. Of course, that's better. But Blake also loved to tell me this story about her teacher who taught her to be a guide. Loves to tell this story that he actually did a successful session, forced guide therapy session, in the middle of a parking lot under the shade of a single tree. So it is very possible to do this with a single tree, even in the middle of a parking lot, you can have this connection to nature. And I think, again, kind of reinstating why urban nature is so important and why we have to be careful not to write off urban nature as not quote, unquote, real nature or effective nature for these kinds of things. A lot of these sessions can take part in parking lots with single trees, if you're really forced to. But otherwise, backyards, urban parks, manicured gardens, you know, there, as long as it's some kind of natural setting, you can actually start to feel a lot of these benefits, you know, and if you have access to a beautiful old growth forest, of course host your session there. But even if that's not possible, you can still feel the same kind of sense of grounding that other places are able to offer.

[00:19:12] Speaker A: So, yeah, I think that's obviously brilliant advice. You know, if we're just viewing, take out the word forest, only nature is the therapist. And wherever we can find that, you know, little Bit of nature. If it's only a little bit, that's okay also. So I think that's excellent advice.

You have some really interesting case studies that you featured in this part of the book. Can you talk us through some of those, Nadina?

[00:19:40] Speaker B: Yeah, there are.

There's quite a number of them. And one of my favorite ones is this idea that trees, through this specific kind of technology called geolocated sound, can actually talk to us.

It was this project by theatre director Puk van Dijk in the north of Amsterdam. Amsterdam north is this rapidly developing neighborhood which I think a lot of post industrial cities can relate to. It's an area that is really dealing with, you know, rampant changes, gentrification, drug use, pushing out certain demographics, pushing in a new demographic, dealing with, sadly, a lot of deforestation to make way for a lot of this development. And Buch van Dyck moved to this neighborhood after she had a very nomadic childhood, lived all over the world. And when she had a child of her own, she wanted more stability. And she looked for stability at her tree neighbors, the ginkgos, the ashes, the oaks, the maples that she shared her new neighborhood with. She was really inspired by them and she wanted to understand her neighbors more. So she started to interview some of her human neighbors and she started see a lot of parallels, right? She would talk to a new neighbor who was a retired bodybuilder, and he was complaining about the fact that this highway that had been expanded was causing his asthma to get worse and worse. And he was dealing with a lot of issues. And she was wondering, she was like, I wonder if the trees that are planted next, that highway are dealing with similar issues. She talked to another neighbor who complained how lonely she was, especially during the pandemic and afterwards too, that she missed these talks with a lot of her neighbors after they had passed away. And she saw this tree in the middle of a square that was all by itself. And she was like, I wonder if that tree deals with loneliness in the same way as humans might be able to relate to. Long story short, she created this immersive audio tour of these six talking trees. She called it the Giants of North. And she was able to use a lot of these interviews that she had done with human neighbors and translate their stories to these trees. And she actually used local voice actors, actors that were from Amsterdam north, to put on the create these characters and put on these voices for these trees. And it didn't work like a typical audio tour where you would have to scan a QR code every time you're at a new stop, you were just able to press play, go on this walk. And the gps, your GPS location would actually guide you either to the right or either to the left based on where you were. And if you were close enough to one of the trees, it would actually start talking to you. And this just meant for such an immersive experience because, for example, in this tree that was dealing with a lot of pollution, it actually started coughing before you could even see it. You would start to hear this coughing, you would turn the corner and there was the tree right next to the road, dealing with these issues. And I just thought it was such a fantastic example to, in a really creative way, show urbanites the plight of city trees and what they're dealing with and at the same time provide people that, yeah, that normally wouldn't have that kind of. That interaction, that connection with trees to be able to relate to them more. And I think that's something so critical that we've touched on in the past. The more you're able to understand and relate to something, the more you're able to care for it and ultimately protect it as well.

And as I write in the book, this tour was so successful that they're working to make it a permanent installation. And in fact, the chief urban planner of Amsterdam has deemed the Giants of North audio tour as mandatory listening for everybody in his department.

[00:23:30] Speaker A: It's such a wonderful story and I haven't been. I haven't been to Amsterdam for an awfully long time, but really, it makes me think I should go back to Amsterdam definitely just to hear the trees talk.

[00:23:42] Speaker B: Unfortunately, the trees only speak Dutch at the moment, so you'll have to a little bit. But I would love. I said that book right away. I was like, you need to get a translated version of this because this would be. It's also just like, I've talked to interpreters so people that their work, you know, whether they work for national parks or museum, their work is to translate, you know, disseminate knowledge and information to the general public. Could be history, it could be natural history, all kinds of different things. I was like, this is such a beautiful way to do interpretation. Like, it's so replicable. Like, I would love to see something like this in every city around the world, like, even just as a tourist attraction. I think it's such a cool idea.

[00:24:23] Speaker A: I think it's a really cool idea. I mean, I think. Thinking out loud, really, Nadina, I think that those trees, like my birth city of Dublin, you know, those trees that are by the canal in Dublin. Surely they can tell not only their own experience of the changing, you know, the changing sort of sights and scenes and vibes of Dublin over the last, you know, couple of decades or whatever. So they could probably express like, their own, you know, I'm relatable as a tree, but also give, like, visitors a little bit of the history of that area at the same time.

[00:24:56] Speaker B: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. And that's actually the descriptive text of the giants of north actually starts, I believe it starts with, oh, the things our giants have seen. Because if you imagine these older trees and then they talk about, you know, the bickering couple, the crash between a Vespa and a bike at three in the morning, you know, the child climbing it, you know, all these different things that the history. I mean, if we're lucky, we have trees in our cities that are, you know, centurions, over 150, 200 years old. I mean, these trees were there before we were born and hopefully we'll be there long after we're gone.

[00:25:34] Speaker A: Hopefully. Hopefully. But it's such a fantastic concept and hopefully, as you say, it'll become more widespread, you know, because it is absolutely brilliant.

Heading to Melbourne, Australia, there's also an email, a tree campaign. How does that work?

[00:25:50] Speaker B: Yeah, speaking of projects that are so easily replicable in cities around the world, there is a campaign called the Email the Tree Campaign, but it didn't. It didn't start quite like what it sounds. Essentially, it started. It all started with Yvonne Lynch. She was the head of the Urban Forester and Urban Forestry and Urban Ecology team for the City of Melbourne. And what she was struggling with is that every day she would get emails, she would get phone calls, she'd get stopped in the street, her colleagues would get stopped in the street to get to answer questions about trees in people's neighborhoods. Right, like this.

This tree looks sick. When are you going to look at it? When is this tree going to be felled? When are you going to look at the damage to this tree? This, you know, electrical cable is coming very close to the branches of this tree. All these, you know, questions, you could even call them complaints at times were just coming in mismatched. And the first, you know, question that you would always have to give an answer to was, well, which tree is it? And then would follow this incredibly frustrating conversation of, well, it's across from this address, but it's not that tree, it is this tree. You know, it's a citizen. They might not know the species of the tree. So they would do their best to describe it. You know, it's the one with the trunk and with the leaves and, you know, it was just very frustrating, very frustrating situation for Yvonne and her team.

So what she did is she piloted a program to get an ID number for each individual tree, which they already had. But couple that ID number to. To an email address so that ID number, every individual tree now had an individual email address. So that ID number could be found on a map. You could zoom in, you could find the tree, and then you could immediately see the email address, and you could email your question about that specific tree to that specific email address. And that worked quite well as a management tool until Yvonne started to notice something quite strange, which was that she was not getting complaints and questions about the tree maintenance in her inbox, but rather she was getting sent love letters to the trees.

They were getting all kinds of different notes of affection. You know, things saying like, Dear 10087898, I've always looked out at your branches and your leaves from my window. I sit under your shade. You know, you provided solace to me in times of real struggle in my life. Know, really personal, deep, you know, confessions even about the strength and solace that they got from these trees.

You know, some were kind of quirky and funny, you know, saying that they, you know, were in love with this tree, but, you know, they fell in love with this other tree. And is this considered tree adultery? You know, it was. It just went all over the path. And at some point, you know, initially they, like, they were replying because they thought it was really funny, and they were replying back as if they were the tree. Yvonne and her team. But at some point, it just got so out of hand because it didn't just, you know, it went viral within Melbourne, but then it went viral in Australia, and then it went viral all over the world. So then there were these email addresses set up from other trees in cities all over the world that were emailing the trees in Melbourne, emailing their cousins and their friends across the world. And it just, like, completely, completely bonkers. And it was just such a. Despite, you know, its virality that it had, it was just such a beautiful example that, you know, there is this, I do believe, intrinsic love and affection for the trees that we share our cities with.

But it never really had a way to come out until now. And what I really like about it is that it is so replicable and it would just. It's such a beautiful way to showcase that affection and love that there is for trees. And I keep saying to Yvonne, I was like, you need to, you know, do like the best of, and publish it in a book with beautiful photos of these different trees and these love letters. Because it's just such a beautiful story.

[00:29:47] Speaker A: It really is a beautiful story. It really is. Now moving on to a technology that's used by the US White House and also major tree planting non profits to address health disparities. It's known as Nature Scores. Can you talk us through it, Nadina?

[00:30:06] Speaker B: Absolutely, yeah. So Nature Score is very different to something that, you know, professionals have done in the past, municipalities have done in the past, which is doing an assessment of the greenery that you have in a city. So in the past this was done by viewing something called the NDVI or the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. And that worked really well, but it worked really well for doing one thing which was mapping the greenery in a city. But we know now that the health, that the health benefits that we get from nature is not just greenery. In fact, it also comes in the form of water bodies, of beaches, of open fields, of forests. You know, all these different natural elements play a role in our, in our health. And in this NDVI analysis, things like sand and rock and water actually get a score of zero because they're not green. And we know now from research that these areas do provide health benefits. So Nature Score was developed as an alternative to that. It was developed by a startup in Oregon called NatureQuant. And you can kind of sense it in the name. Their mission is to quantify nature. And the reason why they want to do that is because they wholeheartedly believe that if we can give nature a number, we're going to be better off trying to get the investment for it and find and really fight for its rightful place, especially in urban environments. So Nature Score, essentially what it does is you can pick any static address anywhere in Canada and the U.S. and they're working on Europe at the moment, and you can get your Nature Score. So basically that takes, it takes a radius of 500 meters from around your house. That is the distance that we know from research that the nature is going to have an impact on the health of you living in that specific address at that place. And it gives you a score. You know, 100 is, you know, you're, you're in the middle of a forest, you know, that is, that is, you're in a nature rich environment. 80 to 100, you know, 60, 60 to 80 is something called nature adequate. And Then it goes into nature, I don't know the medium one. And then it goes into your habit, nature deficit, or you're in an area that has nature deficiency.

And all of this is taken into account by many different parties. It's been quite interesting who has started to use this map. Initially, you know, NatureQuant thought it was primarily going to be used for things like municipalities, like deciding where nature interventions should take place and trying to come up with a more equal way of distributing those resources, you know, rather than just distributing, you know, more greenery in areas that are the loudest, which tends to also be the more wealthier neighborhoods because they have more time on their hands to be able to complain about things, really spreading those resources to some of the more often socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods and also nature deficient areas. And that is still one of the use cases. But what I think has also been interesting is it's starting to be used by insurers, health insurers. So looking at, you know, if you live in a nature rich area, we know that you're actually going to have less health issues. So some of the more innovative health insurers are looking at, can we actually help people that live in nature rich areas, can they actually pay a lower insurance premium? Which is a really interesting way to like, further incentivize investment in nature in some of these lower socioeconomic, advantaged, disadvantaged neighborhoods is can we make those things more equal as well? Investing in neighbor in neighborhood greening also means paying less for your insurance. I've heard stories of it being used by police chiefs trying to understand the links between nature in their cities and crime in their, in their cities, which there's really interesting links and not causations, but correlations you can find there as well. And then we're seeing big government institutions like the White House administration, but also big, big nonprofits like the Arbor Day foundation, which you know are one of the biggest tree planting organizations in the world, actually use the nature square map to decide where they should plant and do these greening interventions. Because we know from research that you're much better off planting a single tree on a street that doesn't have any, versus planting an additional tree on a street that already has a bunch. You're just, you're going to get many more benefits, whether that be climate related or health and wellness related from that singular tree. So I think that's really an interesting use case. But I think most importantly, it's looking at nature from a different perspective. It's looking at nature purely from what are the natural elements that are health supporting and deciding our policy decisions based on that information?

[00:35:14] Speaker A: Yeah, that's huge. Obviously, if some of the insurers are taking it into account, that's huge.

Something else that really impressed me was that even lakes could keep us alive longer. I find that quite amazing, as I did the prescription app. Now who actually created this and what does that do?

[00:35:37] Speaker B: Yeah, so Nature Dose is the nature prescription app that was built on top of Nature Score. And essentially how it works is it's an app that works in the background on your phone. So it's not an app that's designed to have you glued to a screen. It works in the background of your phone much like a pedometer or a Fitbit would or step counter would on your phone. And essentially what it does is using your GPS location on that Nature Score map, it basically aggregates so it doesn't hold on to your location data, but it basically aggregates on a daily basis how many minutes you were inside, how many minutes you were outside, and how many minutes you were exposed to nature of those minutes outside.

And what this essentially does is it provides you that nudge, hopefully to get outside more, much like a Fitbit would, to help you reach that 10,000 step goal a day.

The Nature Dose, the best research we have, shows that we need a minimum of 120 minutes, two hours exposed to nature every single week. So that's an average of what, like 17, 20 minutes a day, getting you at that bare minimum, so nudging you to go outside exposed to nature for at least 20 minutes a day. So of course it has the nature square map, which is very granular, is able to show, you know, you get like, you get a full point for being in the middle of a forest, you get a half point for being on a heavily tree lined street. And you get zero points if you're standing in the middle of a parking lot. And that's the difference between outside time and time exposed to nature.

And to your point, Jackie, beaches and lakes also get high points because we know from research that those things are very health supporting as well. And then the question becomes, okay, well, you know, how can we use this app? How can we integrate this? I think for some people it's going to feel a little bit shocking that we now need an app to tell us to go outside. And I would say for the people where that feels shocking to, maybe you don't need it, right? Maybe that's something that's so integral into your daily habits that you don't need something like Nature Dose. But I would argue there's a vast majority of people who do need that nudge to go outside, much like they need the nudge to take 10,000 steps a day. The importance of Nature Dose is it's not just about how many steps you take every day. It's also about where you take those steps a day. And this is a nudge to hopefully take those steps in a nature area so that we can really benefit from all the beautiful advantages that nature offers us. But I also see potential use cases here. For example, like a collaboration, for example, with your mental health practitioner. I talk about a case study in the book where they actually you are using Nature Dose as a warning sign, typically for those that are underage teenagers that are dealing with severe depression and severe mental illness as a warning sign that that information that they haven't been outside in X amount of days is actually being sent to their mental health practitioner to know that they have to do extra checkup and welfare checks on those individuals, which, yes, can feel big brother to some. But we're talking about underage teenagers dealing with severe mental health illness. We want to make sure that they're getting the help that they deserve. Another use case is actually for big corporate partners. Right? In this age of working remotely and working in kind of this hybrid fashion, can we actually encourage employees to get outside, taking walking meetings, getting outside during their lunch break in places of nature? Because we know those employees are going to be more productive, take less sick days, and have less signs of burnout. So I think we're only at the cusp of understanding how we might potentially be able to use this. I think there's a lot of interesting use cases. And ultimately, I think my biggest hope, and I talk about it also in the epilogue of the book, is that apps like this will probably become obsolete one day. In fact, I hope that they do because we'll have created.

We'll have created urban settings and urban environments that are so rich in nature that we don't have to think twice about getting our 10,000 steps a day or our 20 minutes or an hour of nature a day, because it'll become so ingrained in our daily habits and how we move about our daily lives.

[00:39:56] Speaker A: Yeah, I mean, you trigger my imagination again because I'm on the same page as you in that sense, because I have a visual idea of not too far down the line, you know, the urban areas that we talk about that will be very, very lush. And I'm thinking and hoping that the people Living in those areas in the not too distant future will look back at history and go, oh, my God, like, how did people live in those concrete jungles beforehand?

[00:40:26] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah, exactly. I think the thing that's interesting with cities is that I think people are very quick to look back on how cities used to be and be very negative about how they used to be. But the fact is that cities are such a successful social experiment, They've continuously adapted and molded to what the needs and the wishes were of the urban population at that time. Right when the first combined sewer systems were integrated, you know, it was a hallelujah because cities were dealing with open sewers in the canals, with cholera outbreaks. You know, it was, it was, it was dirty and stinky and awful. And combined sewer systems provided, you know, massive improvement to that. Now we're looking 100 years on, we're looking at those systems and being like, in times of extreme rainfall, those can be really, really bad because we can lead to combined sewer overflo flows, which is, you know, having terrible impacts on our water quality and our own public health and safety. Okay. So we're looking at ways that we can adopt more green infrastructure and more kind of sponge city tactics to be able to absorb much of that rainwater so that the combined sewer system in areas where, you know, it cannot be separated because it's too expensive and too difficult. You know, we're able to actually absorb a lot of that rainwater so that the combined sewer system is under. Is under less duress in those areas. I think we have to continuously look at how can we adapt and change to the needs of the urban population in 2024. You know, there was a time with the rise of the car that it was seen as a celebration to have highways smack dab through the middle of our cities. We think differently now. We're seeing, you know, we're having some critical conversations about whether it makes sense to designate so much space to roadways and parking spots. Why would we have them on the ground level? Why can't we put them underground? Why can't we do things like car sharing to reduce the pressure of on the land and instead use that area for public space and ideally green those spaces. So we're constantly looking at changing, you know, the needs and the wants of our urban population. And indeed, to your point, Jackie, I think we're going to look back and say, how do we ever live in those concrete jungles? And we're going to look forward to the future and see hopefully a very optimistic nature, rich urban environment that is so beneficial to every single aspect of human life and all the other species that we share our cities with.

[00:42:54] Speaker A: Absolutely, absolutely. So you and I both feel that way, which is brilliant. But unfortunately, there's a lot of people, particularly younger people that we're aware of, you know, personally and. And just purely through the work that you do and I do, that really lack optimism for the future because of, we'll say, climate change and biodiversity loss. And the world as it is right now, this is something that's a huge topic of today because these people are our future generations and they're in this situation. A larger percentage of them, for example, are maybe, maybe attempting suicide. And as you mentioned about nature dose, of course, in a young person's life, that app is very important because at least whomever is treating their depression or whatever disorder that they're dealing with will actually be able to see. Well, look, you know, you didn't go out in nature for, like, five days or something. It's a huge topic. Gina, what are your thoughts?

[00:43:55] Speaker B: Yeah, I think I try to very much operate from the philosophy that when we look at the world, and specifically at our cities through the lens of nature, we operate from the perspective of abundance and of creation and of hope and of optimism. And I think that's something that natural areas provide. They provide that area for respite, to restore our minds, to find ease and to hopefully find relief from some of the pain that we're feeling. And that's something that I believe is so critical, especially in this age of climate anxiety and doom and gloom, to continue looking at our world through the lens of nature and creating more nature, creating more spaces for nature, for us to interact with nature, for connections with nature. Because I do believe that impacts every single aspect of our lives, that of our parents, our grandparents, of our children, and. And for those of you that are feeling like, okay, sure, easy to say, but what am I supposed to do in my apartment on the sixth floor? I only have a balcony. I would say one that balcony is still. Even if it's only a windowsill, you never know who's looking up at that balcony. Greening that balcony is already providing you with a ton of benefits and also any passersbys. But I would also invite you to look critically at. Where do you spend the majority of your time. I bet you it's probably not in that apartment. It might be on the road that you commute. It might be at your office space. It might be at your corporate campus, your university campus, your child's School, your place of faith, your church. These are all areas and cities that actually tend to be on private ground that we actually have a lot of control over what we can do to change the face of these landscapes. And I would encourage you to get involved with that. Take stock of what's around you, especially within that 500 meter radius of your house. Think local and act locally as well, because that is ultimately, if everybody did that within a 500 meter radius of their own home, our cities would look like a very different place.

[00:46:03] Speaker A: They would indeed. Now, I was going to finish up by asking you for any final words of advice, but I think you've almost just done that yourself. But are there any, any other, you know, little gems that you'd like to offer to finish up?

[00:46:17] Speaker B: Four part series, maybe less advice and more of a little challenge. So I did, I did say to you to take stock of what's in that 500 meter radius, but maybe concretely I'd invite all of the listeners to identify at least 10 flora or fauna species within a 500 meter radius of their home. And if you'd like, you can use one of these apps that we discussed, Earth Snap, PlantSnap, iNaturalist, and get involved a person. The City Nature Challenge, if that's, that's typically at the end of April, beginning of May, which is a fantastic way because then you're not only identifying these species and taking stock of what's around you, but you can also meet other people who are interested in this as well. And you'd be surprised how often if I stopped taking a photograph of, you know, some beautiful flower of a tree leaf or, you know, trying to get a glimpse of some butterfly on my camera. You'd be surprised at how much of an icebreaker that is, how quickly, you know, people notice that and ask questions about it. You know, what are you doing or what are you looking at? You know, it's such a beautiful icebreaker and this beautiful opportunity for social connection, which I think we desperately need in today's world, especially in our cities.

[00:47:39] Speaker A: That's absolutely correct and wonderful advice, Nadina. It has been such a pleasure having our various conversations. And you know, I think that everything that you've said is going to be so useful to listeners and I have thoroughly enjoyed our shots together.

[00:47:57] Speaker B: I really have too. Jackie, thank you so much to the listeners for listening and to you, Jackie, for wanting to spend so much time on these really, really important topics. I hope your listeners found a lot.

[00:48:09] Speaker A: Of value in it and I believe they will. Nadina, thank you so much. This is constructive voices.